How Europe can compete in Generative AI

Why the current approach won't help to create ChatGPT in Europe

The importance of Generative AI can be compared to the emergence of the internet. With the potential to replace search engines and become all-encompassing assistants, Generative AI is set to impact our economy and culture. Europe cannot afford to remain on the sidelines.

As of today, 73% of Foundation models originate from the US and 15% from China. Regrettably, given Europe's current approach, this is unlikely to change in the near future. This article explores why and how Europe must shift gears to compete with the US and China in GenAI.

Europe’s current plan for Generative AI

The EU Commission has allocated a budget of 2.2 billion Euros for “AI, Cloud and Data” as part of its Digital Europe funding program. In addition, the EU has invested 7 billion Euros in High-Performance Computing (HPC) centers to support scientific applications for businesses and academia. Ursula von der Leyen proposed that these HPC centers be made available to AI startups in Europe to train their foundational models.

Several European countries have launched their own national AI strategies. For instance, Germany plans to invest 2 billion Euros in AI over the next two years, with the goal of establishing 150 new university labs dedicated to AI research.

Germany’s LEAM (Large European AI Models) has presented a comprehensive proposal for a European AI infrastructure. The proposal outlines the establishment of a public-private partnership and an investment of $400 million in a high-performance computing center in Germany. The objective is to develop large foundational AI models that align with European values.

France has allocated 2.2 billion Euros for its National AI Strategy, a significant portion of which will be directed towards education, private sector training, and subsidies to integrate AI into the economy.

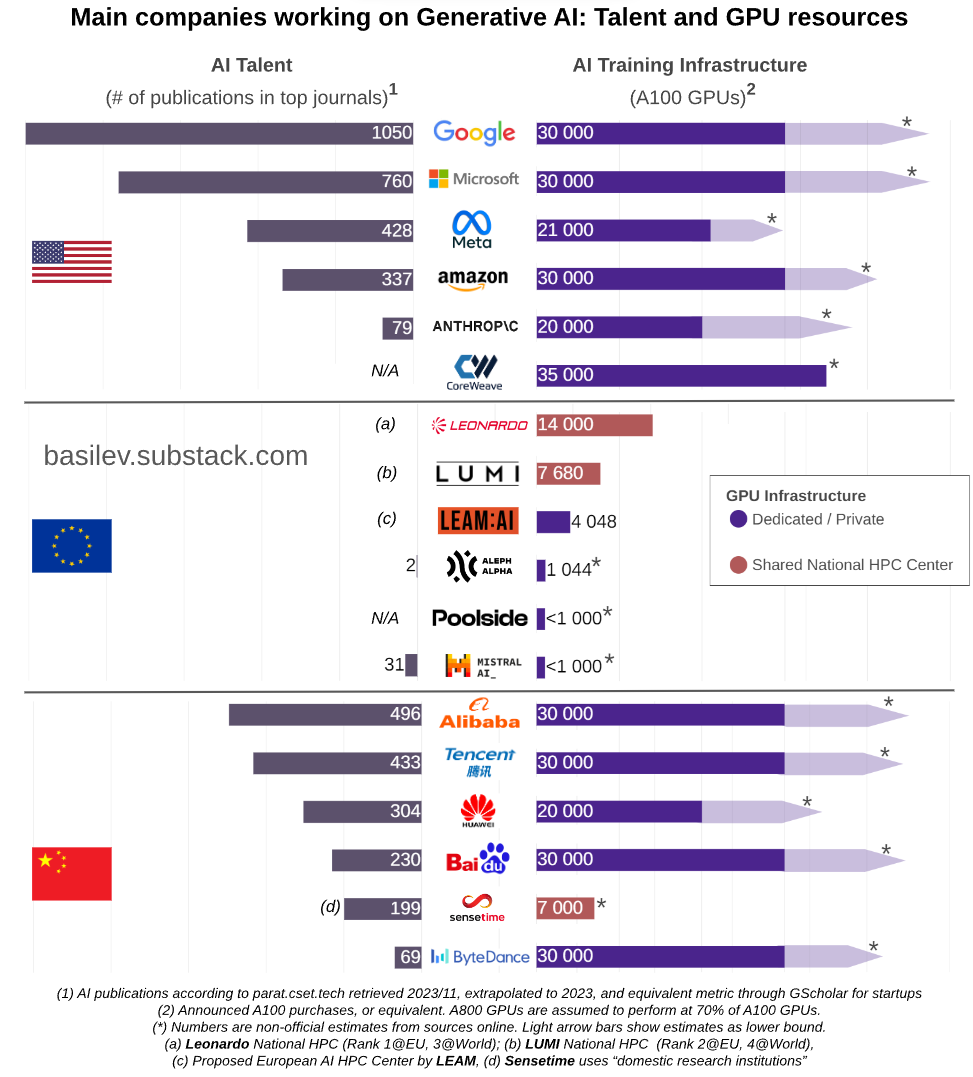

Among these national plans, common themes emerge. A large part of public investment is dedicated to sustaining Europe’s global leadership in training top-tier engineers. I commend such investments, as they have enabled Europe’s universities to remain competitive with their counterparts in the USA and China in terms of AI research output.

… Yet the continent faces a severe resource deficit

According to the OECD, American VCs will invest $67 billion in AI by the end of 2023, which is 8 times more than Europe’s $8.2 billion. I explored the root causes of this disparity in my previous article.

In a world where top AI engineers earn over $1M per year at firms like OpenAI, the underfunding of local startups leads to a significant brain drain to the US after graduation.

Taxpayers’ resources are spent training exceptional AI engineers who ultimately join US companies. Instead, more of that funding should be allocated to support local startups and retain talent.

Training high-quality AI models also requires substantial infrastructure. Reportedly, OpenAI trained GPT-4 for 100 days using 25,000 A100s chips, with the cost of the hardware running into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Consistent access to training infrastructure is necessary to keep models updated with the latest online content. This training can become costly for companies that do not have their own specialized data centers.

Even with the most powerful HPCs provided by the EU, European startups aiming to train a model equivalent to GPT-4 would require nearly half a year. However, numerous other organizations are also on the waiting list to use those HPCs for applications ranging from climate modeling and materials science to genomics.

Compared to their US and Chinese competitors, Europe’s GenAI startups own an order of magnitude less GPU infrastructure. Efforts can be made to optimize the effectiveness of GPU use, but this will likely not be enough to compete commercially with “GPU Rich” companies like Google and Microsoft.

This disparity isn't solely due to European VCs' lower investment levels. The absence of a European cloud provider to support native AI startups with infrastructure for a stake in their LLMs exacerbates the issue.

Moreover, the reliance on American hardware for data centers presents a vulnerability. The US has already shown readiness to stop GPU exports to maintain its technological lead. Europe's dependency will persist, necessitating massive investments in Nvidia or ARM GPUs, until it establishes its own semiconductor industry.

Nvidia, meanwhile, has soared to a trillion-dollar market valuation, dwarfing Europe's top tech firm, ASML, the manufacturer of EUV lithography machines used by TSMC to produce Nvidia's chips.

In the current course, US cloud providers will continue to monopolize the EU market, reaping profits from deploying their models. This advantage fuels a self-reinforcing cycle of improvement, potentially leaving Europe trailing further behind.

How a European GenAI strategy could look like

Pool resources

In the 1980s, Jacques Delors envisioned a European single market, predicting that integrated national economies would lead to specialization and enhance export capabilities. This specialization has proven successful in sectors like automotive, aerospace, and telecom, with the same potential for cloud and information technology.

But unlike previous industries that streamlined gradually through market dynamics, AI requires proactive EU planning and funding to catch up and capitalize on first-mover advantages.

In the race to attract elite talent and secure expensive AI infrastructure, size matters. Thus, Europe should concentrate its investments on nurturing a very limited number of potential market leaders. A viable strategy could involve selecting frontrunners through European AI Grant competitions, similar to AI Grant competitions organized by the Chinese government.

Buy European Models first

The EU is already funneling billions of Euros in the deployment of AI technologies through vehicles like the European AI Fund. We should make these subsidies contingent on purchasing home-grown European solutions. This could provide the necessary impetus for European enterprises to prioritize local AI models, even if they currently lag behind their American counterparts in performance.

Economic nationalism has demonstrated success in various contexts. The United States, through its Inflation Reduction Act, and China, with its powerful Great Firewall, have both supported their domestic industries. China's state backing of its underdeveloped semiconductor production in response to US export restrictions serves as a compelling example of this approach. The EU should consider adopting similar strategies to protect its crucial industries.

Regulation, not Legislation

Europe should favor adaptive regulatory frameworks rather than rigid legislative ones, particularly during the nascent stages of AI development. The AI Act, conceived in 2021 and slated for implementation in early 2026, risks being obsolete upon enforcement and is already casting a pall over innovation, as evidenced by concerns voiced by the European tech community. The UK has opted for a pro-innovation stance, a move that undoubtedly influenced OpenAI's decision to establish its European base there, favoring a dynamic environment over a prescriptive one

By contrast, China's government, renowned for its stringent control over online information, is nonetheless demonstrating an unexpectedly forward-thinking and flexible approach to GenAI regulation. By fostering close collaboration with the domestic AI sector, Chinese regulators are spearheading the development of interoperable standards, such as the protocols for implicit watermarking to identify AI-generated material.

I am not advocating for a US-style laissez-faire, as I do believe that AI comes with serious risks. An international consensus on regulation is necessary, and I support Van der Leyen’s intention to create “the equivalent of the IPCCC for AI”.

It is incumbent upon EU policymakers to have a clear understanding of the tradeoffs in their regulation. The compliance costs are only worth bearing if laws are timely and adaptive to GenAI’s fast-changing nature.

A holistic view of the ecosystem

Building the model or application layer is not sufficient if Europe wants to maintain its sovereignty. As Andreessen Horowitz noted, infrastructure providers (Cloud and Chips) aggregate most of the AI value chain.

There is no strong GenAI without a strong Cloud. Both layers depend on each other, to the extent that every large Cloud provider has chosen to develop their own GenAI model. This synergy is underscored by the alliances between OpenAI and Microsoft, and Anthropic’s partnership with Amazon, each witnessing multi-billion-dollar investments.

Vertical integration reaches down to the chip layer, since Google is developing its own GenAI hardware, and NVidia has started offering its own cloud service. Software tooling, such as NVIDIA’s CUDA libraries, fortifies these companies' dominance, establishing formidable barriers to entry and making the emergence of a new ecosystem more challenging.

Nevertheless, Europe has the requisite talent to forge its own technological path. The continent needs an audacious, holistic strategy for its IT sector — a strategy that encompasses every tier of the infrastructure, from semiconductor to cloud and foundational GenAI models. I will approach these topics in future articles on my substack.

EU Commission and States need to act now

Europe needs a step change in its current framework and thinking around GenAI. Given the amounts that need to be invested, the continent would require a massive, centralized approach.

Europe also needs to be patient and diligent in her support for her champions. Strong lock-in effects of existing cloud providers will be hard to dislodge.

GenAI represents a major architectural shift in computing, which is a rare opportunity for startups to get a leg up on incumbents. The last major shift was the rise of mobile and cloud, and one can only speculate on the potential outcomes had Europe fully capitalized on that technological wave.